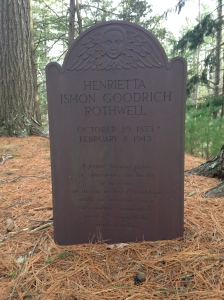

The headstones and shared foot stone of Mary Elizabeth Taylor Goodrich (left) and Henrietta Ismon Goodrich Rothwell (right)

I was recently at the Evergreen Cemetery in Kingston, MA. Truly a lovely spot and a fine example of the 19th century garden cemetery movement, replete with a reflecting pond and fountain, albeit the latter not working on a cold December day. I had gone there in search of the grave of my house’s original owner, Capt. Richard Francis Johnson, but rather disappointingly, I found his monument almost immediately. This left me plenty of time to wander and meet the other residents of Evergreen. After an hour’s walking, I spied a site that intrigued me. Atop one of the cemetery’s highest points, in a small, idyllic clearing amidst overgrown pine trees, were two matching stones belonging to Mary Elizabeth Taylor Goodrich (1846-1934) and Henrietta Ismon Goodrich Rothwell (1873-1943). The shape of the headstones, along with their angel carvings and shared foot stone, were reminiscent of those made in the early colonial period. I liked Mary and Henrietta immediately, women with antiquarian sensibilities much like my own. Clearly they were mother and daughter, but where were their husbands? Were there no other children or siblings? The placement of the stones indicated that this was meant to be the final resting place of only the two women, no one else need apply. Upon closer inspection, I read the most curious epitaph on Mary’s grave, written by a daughter who both knew and loved her well. It read:

We pledge our love and

loyalty to little Mother

for her epic self-control

and gentleness, her dear

whimsical sense of humor, her rare

tenderness and her

undaunted spirit.

Mary was certainly placed on a pedestal, both figuratively and literally, far above the madding crowd, even in death – buried in one of the choicest spots Evergreen had to offer. But who was this daughter that chose to lie for eternity not with her spouse but with her beloved mother? Henrietta’s own epitaph described her “intuitive sense of mother’s immediate need of sympathetic understanding.” A close bond assuredly.

There was a story here…

What I expected to find when I began researching Henrietta and Mary were two prominent local women, probably Mayflower descendants, who could be found on the roles of many social organizations. I would not have been surprised if I discovered they were members of Kingston’s Jones River Historical Society. As for their spouses, perhaps Mary’s was missing because he had been lost at sea, not an uncommon occurrence in a seacoast town, even in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Henrietta’s? Well, maybe WWI.

What I found is something completely different – and the reason one should never assume. Neither woman, as it turned out, was a native of Massachusetts – both hailed from Michigan. Mary Elizabeth Taylor, or “Mollie,” as she was known as a young woman, was born in 1847 in Ann Arbor to Rev. Charles C. Taylor and Henrietta Smith. On May 26, 1869, at the age of 22, Mary married Charles Miller Goodrich in Kalamazoo. The couple started their lives together living with his sister, Albertine Goodrich Hurlbut, and her husband, Dwight, in Grand Rapids. Charles M. Goodrich was a steamboat agent and had a pretty hefty net worth for a young man at the time. Their daughter (and only child) Henrietta, called “Nettie,” was born four years later, on October 29, 1873. By 1880 the Goodriches were living in Evanston, IL where Charles was a grain commissioner. The family was firmly ensconced in the upper middle class, even employing a live-in servant.

Charles and Mary Goodrich must have believed strongly in education, for Henrietta graduated from the University of Michigan in 1894 and went on to receive a master’s degree from the University of Chicago in 1898 – no small feat for a woman at the time. Her thesis topic, “Laboratory Methods in House Sanitation, together with an outline of Class Room instruction,” would become much of her life’s work.[1]

A short year after Henrietta’s graduation, her father, Charles M. Goodrich, died in 1899. He is buried in the Fulton Cemetery in Grand Rapids, MI (1st mystery solved). Whether Henrietta was already living in Boston and sent for her widowed mother upon learning of her father’s death, or if the they decided to move East together, I simply can’t know. What I do know is that in the first decade of the 20th century the two were boarding together at 2 Acorn Street in Boston’s Beacon Hill neighborhood. Henrietta had become the protégée of the founder of the Boston School for Home Economics, Ellen Swallows Richards. Henrietta worked as a director of the school until 1902 when it became the Department of Household Economics at Simmons College.

Home Economics in the early 20th century was a popular movement. It incorporated the teaching of nutrition, sanitation and finance. Proponents hoped to raise domestic work to the level of a profession. Henrietta believed that home economics should be taught in all public schools, from kindergarten through high school, to both boys and girls.[2] So, if you wanted someone to blame for the plaid corduroy vest with the polyester lining you were forced to make in middle school, you’ve found her (or perhaps that is only my issue).

From 1902 until 1911 Henrietta was the Secretary to the Women’s Educational and Industrial Union (WEIU) in Boston, an institution established in 1877 to help women in the city, especially those in the working class, deal with a myriad of social and economic problems. During her tenure at the WEIU, Henrietta “organized municipal enterprises and urged labor legislation” [3] It was while she was employed here that 39 year-old Henrietta came into contact with a wealthy Irish-born industrialist and widower named Bernard J. Rothwell. Rothwell was one of Boston’s most important constituents during a time when the Irish were becoming politically powerful. He was not only the president of his own company, Bay State Milling, he was also the president of the Boston Chamber of Commerce and chairman of the Boston Immigration Commission. Despite a difference in age (he was 14 years older), of religion (he was Catholic) and of education level (he had not attended college) the two found enough common ground to become engaged. Of their proposed union the Boston Globe wrote:

“If the Chamber of Commerce and the Women’s Educational and Industrial are to be allied in the marriage of Miss Goodrich and Mr. Rothwell, a force will be created that nothing in Boston can stop.” [4]

The two were married on Tuesday, November 28, 1911 at the church of Mary Immaculate of Lourdes, Newton Upper Falls, MA. After what must have been an extended honeymoon (their marriage announcement indicated they would not be “at home” until March 1, 1912), they moved into a house they named “Sunnyside” in Needham, MA. [5] Conforming to the conventions of the time, Henrietta most likely stopped working, at least stopped working for a salary. She now was what she had so often taught others to become – a well-educated woman running a household and directing domestic help, using all her home economics know-how. She did retain some of her independence, however. A 1925 passport application indicates she headed to London for “travel and study” for two months alone.

Mary Taylor Goodrich moved with her daughter into her new home. Bernard J. Rothwell’s son, Paul T. Rothwell, was already at the University of Wisconsin by this time and so did not become part of the newlywed’s household. After a few years the family moved once more, to a prestigious address in Boston’s Brahmin Beacon Hill enclave at 34 West Cedar Street.

The Rothwells show up in the usual social calendar events in and around Boston. They also purchased a house in the Island Creek neighborhood of Duxbury, MA. It may or may not be a coincidence that Cardinal O’Connell of Boston also had a home in the vicinity. The Rothwells’ house was built in 1804 by Isaiah Bradford, a descendent of Gov. William Bradford. They used it exclusively in the summer and became members of the Duxbury Yacht Club. Bernard Rothwell’s son, Paul, and his wife also visited, staying in an outbuilding the family dubbed the “playhouse.” [6] It was here that Mary Elizabeth Taylor Goodrich passed away on September 23, 1934 of a stroke at the age of 88 [7]. Her death in Duxbury may explain her burial in Evergreen Cemetery in Kingston, MA – just one town away. My guess is that there was no comparable spot in Duxbury’s Mayflower Cemetery to the lovely ridge on which Mary was buried in Kingston. And, I have to say, if a burial plot were to be designed by someone with a master’s degree in Home Ec, this one would be it – it is neat, clean and orderly. Once Mary was in Kingston, it was most likely a forgone conclusion that her daughter would follow her.

Henrietta Ismon Goodrich Rothwell died a mere nine years after her mother, on February 8, 1943, in her home on W. Cedar Street at the age of 71. [8] Her body was brought to Kingston and laid to rest next to her mother, with the epitaph:

A jewel beyond price

so courageous so loving

so gracious

so warm in her friendships

with an intuitive sense

of mother’s immediate

need of sympathetic understanding.

Henrietta’s husband, Bernard J. Rothwell, survived her by another five years, passing away in 1948. He is buried in Forest Hills Cemetery in Jamaica Plain, MA (2nd mystery solved), a perfect spot for a man of his economic stature. Bernard’s first wife, Emily Taylor Rothwell, was buried at Calvary Cemetery in Dorchester and if I were to look into it, I may find that she was moved to Forest Hills to be by his side.

And now their story is told.

Footnotes:

[1] University Records, vol 3 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1899).

[2] Susan Strasser, Never Done: A History of American Housework (New York: Holt & Co, 2000), 207 and Henrietta I. Goodrich, “Practical Experiments in Home Economics: the School of Housekeeping,” Journal of Home Economics, Oct. 1911, 366-367 and Everybody’s Magazine, vol 21 (1910), 377

[3] The Michigan Alumnus, vol. 19 (Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Alumi Assoc. 1913), 181.

[4] Boston Globe, “Editorial Points,” October 11, 1911.

[5] University of Chicago Magazine, vol 4 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1912).

[6] Dorothy Wentworth, “The Isaiah Bradford House” Drew Archival Library of DRHS.

[7] Duxbury Town Report, 1934.

[8] Boston Globe, obituary, Feb. 10, 1943

All US Census Records, passport applications and city directories, etc. were accessed through Ancestry.com.

My name is Bonnie Rothwell Walsh and I live on Hounds Ditch Lane in Duxbury, Mass.

My Great Grandfather was Bernard J.Rothwell. Although i never met him I feel I knew him so well. Thank you for you article on his wife Henrietta. Its always so amazing to hear the stories of our loved ones.

LikeLike